Flatten your teams

Collaborative leadership as a way to drive research and innovation

15 years ago, while I was straining to pay attention to an audio-only teleconference, it hit me. At that time, online video didn’t really work, so you had to really listen carefully to what was being said. In this case, doing so was particularly painful.

It was one of those meetings where the discussion goes round and round. It was more like a ping-pong match than a discussion. Two sides of a debate just hitting the ball back to the other.

Out of frustration, I called on someone who had been quiet until then. “What do you think?” I asked her. I thought maybe I should not have done that. I was putting her on the spot.

But I was wrong.

She delivered a balanced, creative solution idea. The rest of the discussion faded away, and even though I was just listening, I could tell that the energy of the team had increased. That moment taught me something about teams.

Flat teams are more innovative

In a 2025 Nature commentary, David Budtz Pedersen makes the point that great science happens in great teams. This immediately raises the question - what makes for a great team?

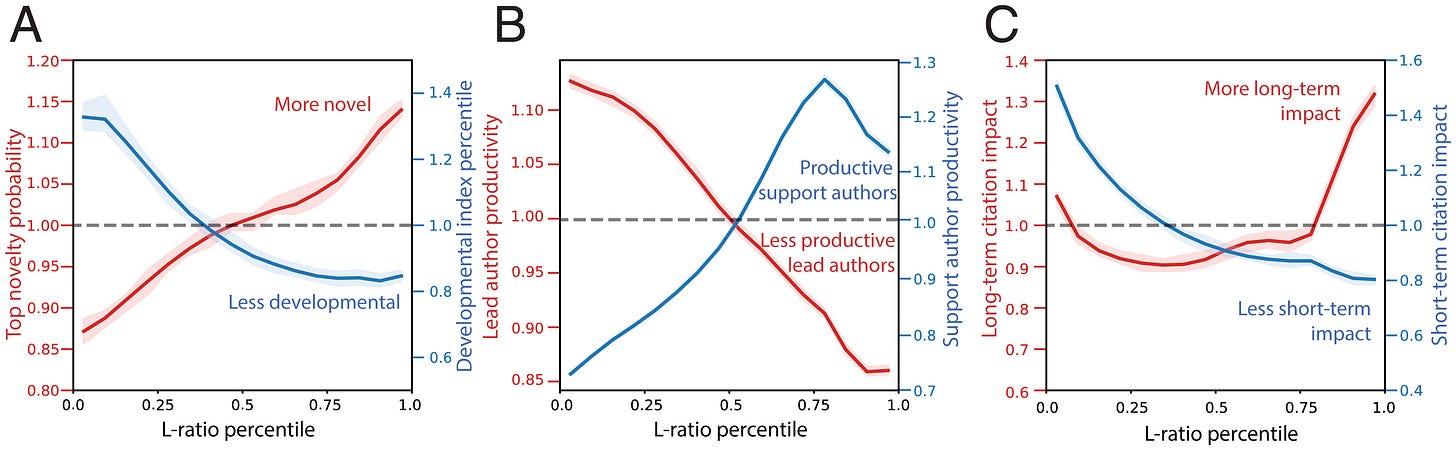

A study in PNAS found that teams with more leaders and a flat structure are more innovative and have greater long-term impact. Teams that are structured in a more hierarchical way, a “tall team” with one or just a few leaders and everyone else in a support role, are not surprisingly best for the careers of the leaders but not great in delivering long-term impact.

That is a nice piece of research, but how do you make a team flatter, especially when it is a tall team?

After the call on that morning 15 years ago, this question, while not well formulated as precisely as above in my mind at the time, became a quest for me.

Meetings and working in a team often feel like frustrating wastes of time, but here was an example where a nearly infuriating meeting became a powerful moment of creativity that energised everyone in the meeting. A worthless meeting was made worthwhile.

My quest has been to figure out how to get teams to be creative, like on that day, both in terms of ideas and problem-solving. I thought that if we figure out how to repeat those kinds of moments and apply what we learned to big, ambitious projects, we could achieve the unexpected. Here is what I have found out so far.

Tiny projects

Encourage team members to propose and take on new projects. I have seen this work very well in consortium projects. Some of the most impactful outputs from a project have been led by junior researchers who took the initiative to do something no one else was doing.

One way to create such an environment is to create a process for creating what I now call tiny projects. These are projects that are deliberately not resource-intensive and serve only to test an idea. It is therefore easy to agree to let those who would otherwise be in just a supporting role have the autonomy to propose and engage in new projects. The risk is low.

When I was in training and working in the lab, my mentor, the head of the lab, encouraged such projects. We were allowed to gather preliminary data and then bring it back to the group. This meant that the lab meetings were always surprising and, therefore, energising. Some of the tiny projects did not work, and that was okay. Being able to test and then iterate is a great way to face the unknown. It is a great way to approach complex problems that have defied solution. It is not to say you should abandon the established project plan, but no one leads by following a project plan.

Tiny projects provide a sense of autonomy, which is one of the three needs defined in self-determination theory (SDT). Tiny projects develop new leaders.

Somewhat ironically, when a tiny project gains traction, it motivates those involved to complete the work outlined in the established project plan. Often, the project plan is to develop something such as a dataset that the tiny project will need.

When you allow such freedom, even in a hierarchical project, you begin to develop an adaptive system. Tiny projects function as feedback loops that can magnify the output of the bigger project. If they deliver positive feedback, it tends to compound into something bigger and bigger. This is a characteristic of complex systems, and this is desirable because it builds both capacity and resilience into your project.

Non-science skills

How to make best use of the overload of skill-building advice in books and online

Transparency

Decisions that come from on high, in which those affected do not see the logic of the decision-making, do not promote a sense of autonomy. If, instead, those affected have been engaged or were at least aware of what was happening, you promote a sense of autonomy. No one wants to be in a collaboration where you have to give up your ideas. Transparency opens the door to collaboration. Maybe someone hears about a problem and, even though they are not directly involved, knows from past experience the perfect solution. In an environment that supports their autonomy, they will be more likely to speak up and propose working together to find a solution.

In this way, transparency helps to expose problems and ideas to a broader array of perspectives. It also encourages people with different perspectives to engage more.

“Serendipity comes from differences.” John Maeda

So, the interaction that comes from increased transparency is a key feature of an effective project. Limiting meetings to only those who need to be there is detrimental to the team’s creative potential. An effort should be made to push towards a project culture in which a diversity of perspectives is exposed to the problem or idea being presented.

Simply making opportunities for interaction, however, is not enough.

Facilitated dialogue

Even though I did not realise it, that day was the beginning of a practice of facilitating discussions, so that they become dialogues. A dialogue is more than a discussion. It is an exchange where you build on each other’s ideas. When there is someone in a meeting who is specifically focused on creating dialogue by asking questions like a did that day, it makes the setting safe for a diversity of ideas. Ideally, the facilitator should not have a stake in the discussion other than wanting to help find a solution. The facilitator should also have some knowledge of the topic. This can be anyone in a meeting who is not directly involved.

When I first started in a large consortium project, I attended up to 20 such meetings a week. I became very attuned to the interaction. Since it was mostly audio-only meetings, I became very attuned to people’s voice inflections. I could hear what was not being said. It was odd. I would show up at a face-to-face meeting and only recognise some people when they started talking. What I noticed is that the most senior people hated that. I suspect it was because, without the non-verbal signalling of the senior people in the project, those who were less senior felt more comfortable challenging ideas and proposing novel solutions. Audio-only meetings flattened the teams’ governance structure.

We can’t go back to audio-only meetings, but an attentive facilitator can work to counteract the effects of nonverbal communication that reinforce the hierarchy in tall teams.

Flattening your teams as an act of collaborative leadership

As Xu, Wu, and Evans illustrate in their research, flat teams have much greater innovation potential. Actively pursuing the flattening of your project structure increases the innovation potential of a team or a project.

The thing is that no matter what your role is in a team or a project by encouraging the development of tiny projects, transparency and dialogue, you can lead even the most hierarchical teams towards a flat structure. Doing so is an act of collaborative leadership.

Collaborative leadership is a distributed approach to leadership that operates through iterative cycles of collective sense-making, decision-making, and action-taking among interdependent actors in a system.

As our ability to address increasingly complex problems grows with greater access to data and AI, collaborative leadership becomes even more important. The great thing about it is that everyone can have a meaningful role in making the seemingly impossible possible.

Pedersen, D. B. (2025). Great science happens in great teams—research assessments must try to capture that. Nature, 648(8092), 8-8.

Xu, F., Wu, L., & Evans, J. (2022). Flat teams drive scientific innovation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(23), e2200927119.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000 Jan;55(1):68-78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68.

Archer, D., & Cameron, A. (2013). Collaborative leadership: Building relationships, handling conflict and sharing control. Routledge.

Scott, this is well said and practical. What can you do to make this more widely read by leadership?