How to Turn Too Many Cooks Into a Recipe for Innovation

Making group innovation actually work

We all have a tendency to fear meetings where a lot of different people contribute to the discussion. Keep meetings small. When they get too big we imagine that we will get stuck in a morass of conflicting viewpoints. Where this becomes particularly worrisome is when we have to make a decision together, like you do when you are developing a big collaborative project. You come to a point where you have to decide what you are going to do together.

How do we best bring together people with different perspectives, especially when they all have their own ideas and their own interests?

This is an important question if you are hoping to do something meaningful by developing and implementing a big project. The whole effort could die a whimpering death, before it even starts.

It would be hard to quantify, but I would bet the challenge of bringing people together is why some of the most important and challenging problems go unaddressed.

When people with different sets of expertise do work together well, the advancements that are possible are stunning. So, it is well worth solving this problem of too many cooks in the kitchen. We can address it on a few different levels.

Let them feel heard.

People need to feel heard. It is the essence of empathy. Feeling heard is not the same as getting your way. They want to be relevant. It may be that what they had to say was heard, duly considered and then discarded or molded into something different. That's okay, as long as they felt heard. The thing is, often the ideas and concepts they want you to hear improve our thinking and the quality of the ideas and plans that emerge. When developing a big project we should be eager to hear and feel what as many people as possible are saying.

While making sure that everyone feels heard gives you the latitude to either merge and even eliminate some ideas, it is still likely that you will be stuck with a multitude of possibilities.

The four-day pivot

I was brought into their funding proposal development project late.

It was late on a Friday night and I thought, what the hell, I’ll look through the proposal. As I read through it, it was indeed clear and well written, but I had the sense that something was wrong.

The methods section had details and there was a nice set of objectives and I liked how they had included a way to quantify the objectives. What was it that was missing?

They had built a very nice, close to implementation project building a platform that could shortly after the project be introduced into the field. I was about to reach up and turn off the computer when I realized what was wrong.

The programme they were applying to aims at radical innovation. In other words, new ideas that had not been tried before. High risk high gain projects. Their project was highly credible incremental innovation, building on something that already exists. Proposals sent to this particular programme are routinely rejected for being just incremental.

With four days left until the deadline, I was not sure I was going to be able to help them. I started to send them ideas for what they could add to the project to make it more radical. They were simple three-line descriptions.

The first two weren't feasible. The third one sparked interest.

I then sketched out how I thought it would all fit together with simple text boxes and arrows. That was not completely correct, but it communicated the concept well enough. Then through the process of iterating the drafts with me pointing out sections where the new concept could be more prominent, the result was a radical innovation project that was high risk, but feasible.

Most importantly, there was now a palpable energy in the consortium.

Prototyping is not just for physical products.

We are all familiar with the concept of prototyping. We associate it mostly with the design of physical products. The iconic story is that of the designers of IDEO going to a grocery store and using a plastic butter dish as the first prototype of the Apple mouse.

We think of prototyping as being how a product is refined over time, and that is the most common use of prototyping, but what most do not realize is that prototyping is also useful for:

Communication

Exploration and

Active learning.

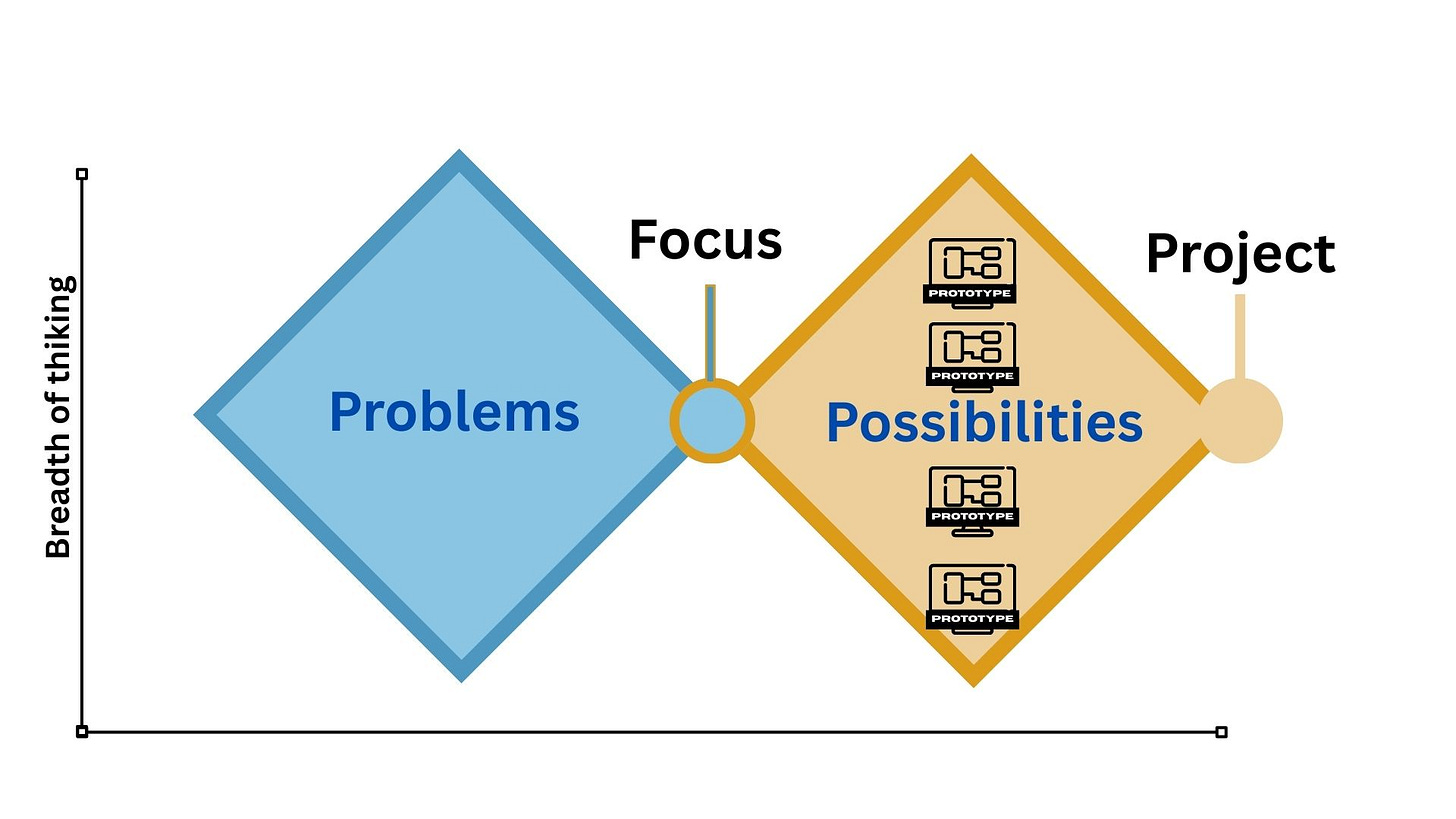

In designing a big project, prototyping can have a particularly important role in exploration and deciding on what the project should be. In the example above, putting out some quick and simple ideas or 'possibilities' led rapidly to a possibility that resonated well with the group. When exploring, a prototype should be simple and rough. If we put in too much effort, the perception becomes that it is a final product, something to be refined not something to consider and potentially discard.

A key to using prototypes for ideation is that the prototype is low fidelity and easy to produce. In the design of a project, that is typically a box diagram showing how things interact or a diagram with swimlanes which show how the project will unfold over time without the rigid formalities of a Gantt chart. Not only does this help by being fast it also means you will be less attached to the prototype.

It is very easy to get lost in a rabbit hole of making a nice figure. Putting too much time in finding the right icons, the right colors and the right types of arrows. The first version you present should be a simple box and text version. This can be something that explains how what your product will work, or it could be how the project elements will interact.

What if the idea is relatively straightforward? Let's take for an example identifying a new biomarker to better target a therapy. In these types of settings it may be better to describe what the future will be like for the different stakeholders involved. You can do this by creating what are called zygotic or science fiction narratives. These are immersive narrative scenarios that help to understand what will be needed to realize the full potential of what the project is producing. When you can infuse scenarios with real-life perspectives, it will reveal aspects you did not anticipate.

When you are creating together, the the thinking of a group goes through divergent and then convergent phases. This is the so-called double diamond model of creativity. Prototypes are used at the peak of the second diamond. They help kick off the process of divergence. They also let people know that they have been heard. Being commissioned to create a prototype means that you were listened to.

Master the art of collaborative innovation.

If you want to be someone who brings ideas together and thereby focuses efforts into projects that can really make a difference, here are some actions you should take and priorities you should have.

Actions

Build your skills for making people feel heard

Practice curiosity by thinking up go-to questions that dig deeper.

Five whys - asking five times why in a series

Just summarizing with an open-ended question.

"How would you make that happen?"

"Tell me more about..."

Listen better, pause before responding.

Listen to what is not being said.

Respond with "Yes, and..."

Develop your prototyping skills

Develop go-to type of graphic for sketching ideas. Keep it simple - boxes, stick figures.

Narratives - learn to write future narratives

An online tool such as Canva and practice sketching while others are talking. Real-time visualization helps others feel heard.

Prioritize

Creating in a diverse group - the larger the better. Prioritize settings where a group with diverse expertise is creating together.

Meetings where there is a dialogue. "No Dialogue. No meeting." A dialogue is where you build on each other's ideas.

Prototyping. When you get stuck, create prototypes or better yet, ask everyone involved to create prototypes. When a meeting draws near its end with no resolution - task everyone with creating prototypes.

Paying attention to the phases of a dialogue. When it gets too abstract, introduce some concrete prototype ideas. Shift from divergent to convergent thinking.

Tackling problems, that others can’t

The most ambitious projects die not from technical impossibility, but from the inability to harness collective intelligence. When we master the art of making people feel heard while rapidly prototyping possibilities, we unlock something powerful: the ability to tackle problems that single perspectives simply cannot solve. The next time you're facing a complex challenge that requires diverse expertise, resist the urge to keep the group small or delegate the thinking to a few. Instead, lean into the apparent chaos of multiple viewpoints. It's often where breakthrough solutions are hiding.

The techniques I describe above work, but they take practice, especially when you're in the middle of a heated discussion with strong personalities and competing priorities.

If you're working on or planning a significant collaborative project, a big project, I'm running a cohort course inside the Learning Cohort Member Paid level of The Big Project Collective. Starting in June where we'll practice these skills and the skills of developing a big together in live sessions. Think of it as a safe space to prototype your facilitation and project development abilities before the stakes get high.

For the month of June join at the annual paid member level and get 1 year of the Learning Cohort Membership at no extra cost (200 euro discount).

Even if you're not ready for the course, start practicing one technique this week: ask "tell me more about that" before offering your own ideas. Small changes in how you facilitate conversations can unlock surprisingly big results.

Great points Scott. Great projects are built by great teams with open communication, encouraging the exploration of diverse ideas. Listening to new ideas from those with a different perspective is the way you grow individually and as a group.

Thanks Michael.