The Meaning You Seek Is Hiding in Plain Sight

How individual and collective mastery make work more satisfying and more meaningful

We become dissatisfied with work because we keep chasing what's new.

Satisfaction and meaning come from mastering the familiar.

"Satisfaction lies in mindful repetition, the discovery of endless richness in subtle variations on familiar themes." George Leonard

What most do not realise is that meaningful work is not just about finding the right kind of work; it’s about how you approach your work.

Medical science is an inherently meaningful type of work, but there are many medical scientists who are dissatisfied and seek to find more meaning in what they do.

In this article, I will show you how switching from a novelty bias to a mastery mindset will increase both your sense of satisfaction and meaningfulness.

Understanding mastery

Mastery is the achievement of comprehensive skill, deep understanding, and effortless competence in a particular domain through sustained practice and learning. It represents a level of expertise where complex tasks become intuitive and performance appears natural rather than forced.

Several key elements characterise mastery:

Deep Knowledge: Masters possess not just surface-level skills but profound understanding of underlying principles, patterns, and connections within their field. They grasp the "why" behind techniques and can adapt their knowledge to novel situations.

Automaticity: Through extensive practice, masters develop the ability to perform complex skills with minimal conscious effort. A master pianist's fingers find the right keys without deliberate thought, while a master surgeon's hands move with practiced precision.

Pattern Recognition: Masters can quickly identify meaningful patterns and relationships that novices miss. They see the wood rather than just individual trees, allowing them to make rapid, accurate judgements.

Continuous Learning: True mastery involves recognising that learning never ends. Masters remain curious, seek feedback, and constantly refine their understanding even after achieving high levels of competence.

Creative Application: Masters can transcend rigid rule-following to innovate and create within their domain. They understand the fundamentals so deeply that they can bend or break conventional approaches when appropriate.

The problem is that if we do not have the patience and perseverance to let mastery develop, we are limited to inferior performance, inferior creativity, and inferior strategies. This is supported by what we know about neuroscience.

Neuroscience of mastery

There are two types of learning: fast learning and slow learning. Studies have shown that in fast learning, existing neural circuitry is repurposed. In slow learning, new neural circuits are formed.

Once we have built the new neural circuits, we can do something that seemed impossible before.

Josh Waitzkin, in his book The Art of Learning, discusses how the masters of the sport of Tai Chi push hands are often thought to possess magical abilities because their opponents seem to fly across the mat without being touched.

When in reality, the masters have laid down neural circuits so they can move very quickly and in ways we don't expect. Waitzkin goes on to explain how, once he achieved mastery, he was able to defeat one of these magical Tai Chi masters who seemed to anticipate every move he made by thinking of a different move until the very last moment. Waitzkin's mastery allowed him the space to think of and implement this strategy in the course of a match. The routine actions and reactions of Tai Chi push hands were automatic for him.

If we constantly default to fast learning in pursuit of novelty, we never develop mastery and all the benefits that come with it. We are stuck with assembling and connecting together existing neural circuits, and that does not promote one of the most sought-after states of mind.

Don't stop at the plateau.

In the process of developing mastery, there are always plateaus. The first one is after what we typically call 'beginner's luck'. George Leonard points out that those who achieve true mastery learn to love the plateau.

For the past 18 years, I have been a consultant by accident. When I moved to Belgium, the idea was to continue working as a physician-scientist. However, due to cross-border work permitting issues that was not possible. So, I started to help researchers prepare proposals for EU-funded consortium projects. It was hard.

Bringing together multiple different researchers and other types of stakeholders, getting them to align, decide and contribute to 100-page proposal was not simple. But then we had some success, and I have now helped develop more than 60 consortium projects. However, there have been times when I was not in love with the plateau. I assumed that the problems that arise in a collaborative proposal development process were just inherent to the process. I tried different solutions, and they did not seem to help much.

I then began to chase shiny objects: different types of consulting that were not about proposal development, in hope that I could walk away from the brain-busting problems of a collaboratively developed funding proposal.

A few years ago, I was managing a small team doing this different kind of work. I realised that I missed the scientifically creative aspects of developing a proposal. So, I reconfigured what we did as a company, and now I am starting to see some of those thorny, persistent problems resolve as I have focused more on proposal development. I was not in love with the plateau. I had abandoned my path to mastery. This raises an important question.

How do we fall in love with the plateau?

Mastery and flow

Mihai Csíkszentmihályi is credited with defining a mental state that we as humans crave - flow.

Flow happens when the task we are doing is just beyond our abilities.

Flow requires a degree of mastery.

When the task is too hard, we have to think too much about what we are doing. In a flow state, mastery enables you to get to that point of being on the edge of constant improvement. Mastery also allows you to be nearly automatic about the aspects of the skill you mastered. Like what Waitzkin describes, this allows you to be strategic while performing at a high level. It is then that we lose the sense of time and develop a deep sense of satisfaction.

Focusing on flow states allows us to at least tolerate the plateau.

However, mastery and the flow it enables do not lead to a sense of meaning. The virtuoso pianist who masters her art does not just play in empty concert halls. She gives performances and touches the souls of those who listen to her. Those moments on stage give meaning to her skill as a pianist. The thing is mastery-fuelled meaning is not something only available to the small percentage of people who achieve virtuoso status. It is available to all of us.

Collective Mastery

Human intelligence is the result of 3.5 to 4 billion years of evolution. That is a time scale that is hard to fathom. The upshot is that we grossly underestimate what is possible with billions of years of evolution. I believe that in that time period the human brain has evolved to be the best possible manifestation for what the human brain is good at. In other words, if we were to build something that matches human intelligence, we would end up creating human beings, including what we think of as flaws or limitations.

You would be right to dismiss this argument straight away with the logic that "ChatGPT is already smarter than me." Therein lies the point. Human intelligence is a generative intelligence made up of 8.2 billion nodes that are infinitely rearrangeable. What's more, the problem of powering these nodes is largely solved.

This means we can think of humanity as one big collective intelligence. The challenge is getting all those nodes to communicate and work together. It also means that, like fast and slow learning in our own individual brains, there are both fast and slow collaborations. Fast collaboration is the small team that quickly makes decisions. It’s the origin of move fast and break things. It relies mostly on experience and hierarchy. Slow collaboration is the deliberate collective thinking. It is about challenging norms and developing something new. It’s solving a problem that, when you first meet with a group, you have no idea how it is going to be solved. However, slow collaboration can be fast. Slow collaboration, just like our brains, is about building new circuits and relationships.

I have witnessed both slow and fast collaboration in consortium projects. Sometimes decisions just need to be made and a few leaders make them. On the other hand, the ability to achieve something can be slow to develop. This is particularly the case when the collaboration is about bringing disciplines together. Once those circuits are formed, a multi-disciplinary collective can solve difficult problems quickly. Slow collaboration is also about investing effort in developing assets such as datasets, which can then be used repeatedly.

Consortia, like individuals, can create group flow. This makes the many meetings that take place in a consortium project energetic and enjoyable. As the relationships build, the ease of challenging each other and building on each other’s ideas rises. The meetings then become engaging whether you are part of the agenda or not.

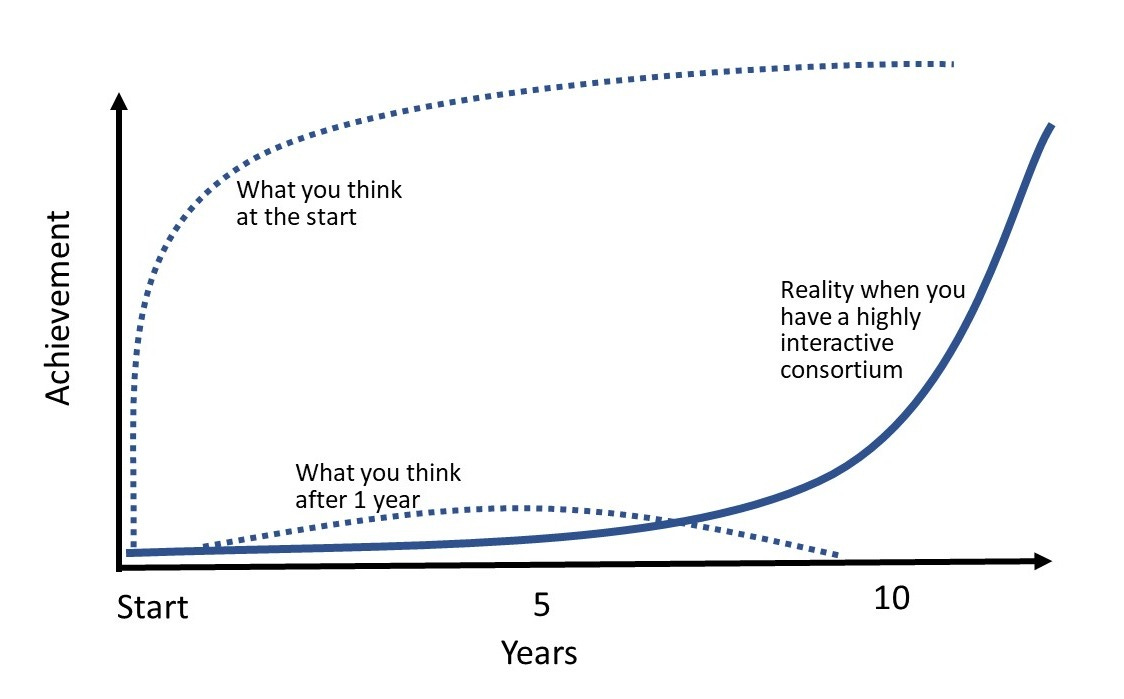

Consortia also go through periods of low achievement or plateaus. This is particularly true at the start of a consortium project.

Consortia that invest the time and effort in building relationships and exhibit patience to move through the inevitable plateaus are the most powerful force for collaboration. This makes the work we invest in collaboration meaningful. While very few of us will ever develop virtuoso-level mastery in a skill like piano playing, by working with others we all can develop collective mastery. We can stand in awe of what we have achieved together, and our sense of dissatisfaction will give way to a deep sense of meaning in our work.

Chasing new things limits our potential.

The problem with chasing new things is that you may end up not developing mastery on an individual or a collective level. For example, the bias towards novelty is what stalls progress in medical science. Instead of doing the hard work to collectively push scientific findings forward into the clinic, a lot of promising medical science languishes.

The one caveat is that in collective mastery, the focus is built around a vision and doing what is necessary to realise that vision. It means that the vision is a sort of a framework for developing multiple new opportunities. The key is that they are all aligned under a common vision. Collectively everyone is moving towards towards that vision.

Turning away from the new and refocusing on the familiar is how you get to the meaning that is hiding in plain sight. This means developing individual and collective mastery:

1. Decide on your mastery pathway.

A mastery pathway should include both individual and collective mastery.

What have you been developing?

Do you feel stuck?

Decide if it is a plateau on a much bigger trajectory.

Everyone should have a skill or asset they are developing on an individual or local team level, and everyone should have at least one project where they are part of a collective mastery effort. Develop your individual skill or asset for use in the collective mastery project.

2. Learn to love the plateau.

a. Recognise the plateau for what it is

Just realising what is happening helps motivate your perseverance. In a collaboration, focus on the collaboration - help each other solve problems.

b. Reflect back on how far you have come.

Remember what it was like when you started. When I started, I was clueless about project development. I had to look up what a 'deliverable' was. To keep a consortium motivated, communicate progress.

c. Cultivate flow

Flow states in their own right are satisfying. Make it a point to get into flow in your work. Enjoy the flow. For a collaboration, invest in facilitating the interactions. Good facilitation can turn dreadful meetings into meaningful experiences.

d. Commiserate with others

Sharing your challenges is a great way to form connections, and connecting in and of itself is worthwhile enough to help you persevere on your current plateau. A consortium project is a great forum for commiserating. It becomes superpowered when you stakeholders that are affected by the problems you are addressing, like patient stakeholders. Their stories leave everyone inspired and motivated.

e. Remember that the new thing you are considering will come with plateaus as well

Keep in mind that when addressing a complex problem in a collective setting, you will need to continually develop new projects, new opportunities, but they should contribute to resolving the problem or the bottleneck that you are focused on.

Your meaning is already here.

The meaning you seek isn't waiting to be discovered in some distant, novel pursuit, it's already present in the work you're doing now, waiting to be unlocked through mastery. When you shift from chasing what's new to deepening what's familiar, you transform routine tasks into opportunities for flow, plateaus into periods of integration, and collaborative challenges into shared triumphs.

Stop looking elsewhere. The meaning is already here, hiding in plain sight.

Expand your ability to see the meaning hiding in plain site by subscribing.